Leah Kaminsky is a physician and award-winning writer. Her debut novel, The Waiting Room, won the Voss Literary Prize. The Hollow Bones won both the Literary Fiction and Historical Fiction categories of the 2019 International Book Awards, and the 2019 American Book Fest’s Best Book Award for Literary Fiction. She is the author of ten books and holds an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her latest book is a collaboration with Meg Keneally called Animals Make Us Human, a response to the devastating 2019–20 bushfires that both celebrates Australia’s unique wildlife and highlights its vulnerability. Proceeds go to the Australian Marine Conservation Society and Australian Wildlife Conservancy.

Leah Kaminsky is on the blog today to tell us about why Animals Make Us Human is so important to her, and how writing it felt like an act of courage and activism. Read on!

If We Could Talk to the Animals: Writing as Activism

I once sent a children’s picture book manuscript I had written to a literary agent I was trying to woo. It was a tale of a shoemaker’s son who had lost his slippers and, while searching for them, asked all the animals he encountered whether they had seen them. In turn, each creature felt so sad that the boy was walking around barefoot that they offered their own ‘shoes’ as replacements. Within twenty-four hours, I received a reply email from this well-respected agent: ‘I’m sick of talking animals in books.’

In one sentence they not only dashed my hopes of becoming a children’s book author, they also nullified thousands of years of narratives about humans interacting with the animal world. The annals of children’s literature are rampant with voluble critters – from Aslan the talking lion of Narnia, a spider’s barnyard friends in Charlotte’s Web, the Cheshire Cat and his menagerie in Alice in Wonderland, and pretty much every fairy-tale ever told.

Animals who speak have also played a crucial role in adult literature throughout the ages, starting with the wily Serpent in the Garden of Eden. The list goes on – Behemoth, the shape-shifting black cat in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, the courageous Bottom with his ass’s head in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Kafka’s cockroach in Metamorphosis. Then there are the brave bunnies in Watership Down, Murakami’s ubiquitous felines, the entire cast of Orwell’s Animal Farm, and the insistent crow in Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers. The appeal of animals in literature lies mainly in the reactions they provoke in human characters, and the strengths and foibles they reveal. Whether giving voice to the oppressed and the silent or asserting moral authority in fiction, animals always have something to say. If only humans would listen.

Descartes claimed it is our right to exert dominion over the beasts. By contrast Montaigne, in his 1576 essay ‘Apology’, cried out against the arrogance of humans who believed that animals, by nature, were devoid of consciousness. His was the lone voice of that era, asking: ‘When I play with my cat, who knows if she is making more of a pastime of me than I of her?’

Throughout the ages, literature’s imaginative response to animals has seen them as beasts of burden, as kin, as poetic voices, or simply as friendly companions. Plato imagined an idyllic time of the Golden Age under Saturn, when ‘man counts among his chief advantages … the communication he had with beasts. Inquiring of them and learning from them.’ When we stare into the animal mirror, we are able to glimpse a reflection of ourselves. The last lines of my latest novel, The Hollow Bones, distil that message, imploring humanity to mend our tattered relationship with nature: ‘The most powerful language belongs to them. It’s the animals that make us human.’

Anne Michaels writes: ‘One book always washes you up on the shores of the next’. In early January 2020, I opened the windows of my suburban Melbourne home, to the stench of smoke which proceeded to invade every crevice. The tragic bushfires were no longer something I felt horrified about from a safe distance– this pungent and urgent reminder now permeated every cell of my being. The smoke choked me with the palpable reality that 3 billion Australian animals had died, and thousands of people were left stranded or homeless. And so, the idea for Animals Make Us Human was born. I wanted to augment the voices of some of our talented writers, scientists, musicians and hear what they had to say about their relationship with our unique wildlife and landscape, inclusive of crucial indigenous voices, the traditional custodians of our lands for tens of thousands of years.

A while ago I found myself on the final shortlist for a lucrative fellowship for a novel set in WWII, which explored the bloody history of man’s relationship with animals. In the final interview the head of a panel of judges asked me: ‘What will be the ‘outcome’ of your project?’ I answered that it would be a book. ‘Only a book?’ they said, looking highly unimpressed. I stood there like a rabbit stunned by the headlights of an oncoming car. Only a book? I’m usually that person who can’t think of a comeback until it’s too late, but this time I knew already that I had nothing to lose. I stood there defiant, galvanised by the imperative of raising my voice for the voiceless; the possibility that activism on the page can and will engage readers and drive change. I stared right back at them: ‘The Nazi’s knew the power of a book. That’s why they burnt them.’

I didn’t win that coveted prize, but it sure felt good that I had finally found the courage to speak up – for the animals.

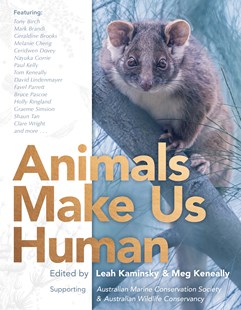

—Animals Make Us Human, edited by Leah Kaminsky and Meg Keneally (Penguin Books Australia), is out now.

Animals Make Us Human

A response to the devastating 2019–20 bushfires, Animals Make Us Human both celebrates Australia’s unique wildlife and highlights its vulnerability.

Through words and images, writers, photographers and researchers reflect on their connection with animals and nature. They share moments of wonder and revelation from encounters in the natural world: seeing a wild platypus at play, an echidna dawdling across a bush track, or the...

Comments

No comments